To what extent are we living in an ‘eternal present’, with a loss of connection to the past?

The inevitable connection

Abraham Lincoln said, “Fellow citizens we cannot escape history”. By history, I understand that he meant the past. Indeed Abraham, the past is inescapable. Every single thing in our present-day world is here as a result of what happened before us. The constitutional monarchy Britain operates under being a result of the principle established through the English revolution of the importance of parliamentary power; the fact I am encouraged to wear flowery dresses whereas my brother is encouraged to wear manly suits being a product of previous generations’ mentality that to be feminine is to be seen as fragile, elegant and beautiful; the institutional and systemic racism that pervades being a scar from slavery and colonialism. The list goes on. My point is that the infrastructures and mentalities we inherit from the past explain why our present-day society operates as it does. This principle applies to every single period of time, as periods of the past do not exist as isolated bubbles, but as one very large, complex spiderweb connected to each point in time, including the present. As such, the prospect of there existing no connection to the past seems preposterous. Figure 1 illustrates this point.

So, we have a connection to the past whether we like it or not, question answered now? Wrong. A connection with the past includes an understanding of what happened, how society worked and what people at the time thought. Essentially, this is what the study of history seeks to accomplish.

So, in this context, what is an ‘eternal present’?

Living in the eternal present means living with a lack of concern for the past, with an absence of a relationship with the past. But why is an eternal present of this kind undesirable? Howard Zinn highlighted the danger when he said:

“History is important. If you don’t know history, it is as if you were born yesterday. And if you were born yesterday, anybody up there in a position of power can tell you anything, and you have no way of checking up on it.”

If Boris Johnson were to say tomorrow in his 5pm briefing “historically, people wearing pink shoes are the carriers of viral diseases”, and we had no way of checking up on it through the study of history, Boris’ followers (and the UK at large) might unjustly turn against wearers of pink shoes e.g. by locking them inside. A silly example, sure, but true in the sense that access to the past and subsequent connection to it allows us to assess claims made in the present and not give people in positions of power the ability to implant ideas in our mind without factually grounded justification. Therefore, while a connection to the past fulfils the appetite of people who wonder “what came before us?”, it also has a practical importance that prevents disproportionate power being given to leaders and further (linking back to Figure 1) understanding the nature of the present.

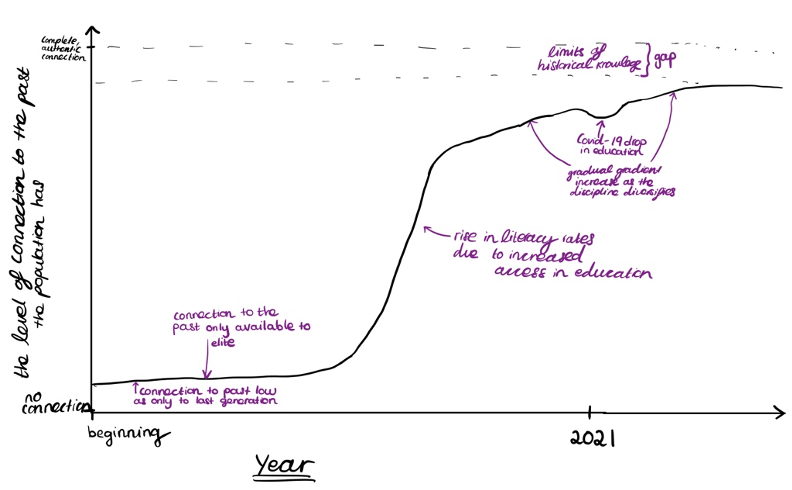

To break down the extent to which we have a connection of this type with the past, I constructed a graph (Figure 2), illustrating how the level of connection to the past has changed over time, where it stands now and the limits of this connection.

Low levels for a long time

For the average person 500 years ago, the principle of performing tasks as they came was an ongoing necessity. A reality riddled with war, pestilence and famine meant that a person’s everyday activities were necessary responses to the threatening conditions of their present, with little time to consider the past. Even if the average person desired to connect to the past and actively attempted to do so, they had no means of doing so beyond the limited recent history of their family passed down through folk stories and word of mouth (which has room to become myth-like, and become distorted) due to the minimal/ non-existent education and literacy rates (standing at c. 5% in 1475). Even up until 1800, the percentage of the illiterate population was c. 90%. All of this meant that access to the past and therefore a connection to the past was only available to that exclusive elite group occupying 10% of the population who could afford to ponder what happened in the past and who had the means to do so. Thus, for a very long time, the majority of people in the past had no choice but to live in an ‘eternal present’, with minimal connection to any sort of past.

The gradient increase

These days, many have the luxury of relative comfort and the privilege of education due to developments in technology and increased income distribution. Currently, the adult literacy in the UK is edging on 100%. In 2016, the global literacy rate stood at 86.25% and only shows sign of increasing as education infrastructure is built in more communities. Furthermore, 51% of the global population uses the internet, which has endless resources for studying history. All of this leads me to say that through rising literacy, access to education and relative comfort, an education in history can be provided, allowing a great proportion of the population to look beyond the ‘eternal present’ by establishing a connection with the past. Thus, the gradient on the graph in Figure 2 increases rapidly, as access to education and literacy rose.

The short way of saying all this is:

- Studying history gives us access to the past

- Access to the past helps us understand the past

- Understanding the past enables us to create a connection with it

- More people can study history nowadays

- Therefore, more people have a connection to the past.

Surely the question is answered now? No. Just studying some form of ‘history’ in a school setting or online does not mean all of ‘the past’ is understood and connected to.

The plateau

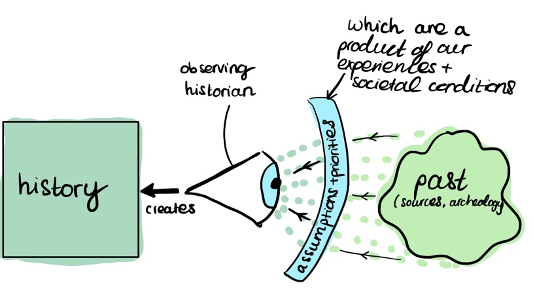

Even if we are studying history, if we are only studying certain aspects of it then our connection to the past is limited. First, the public can only establish connections with those parts of the past on the historical menu. Historians create this menu. Naturally, historians’ study historical episodes they deem ‘relevant’ or ‘interesting’. The kind of things one finds interesting is often determined by their experience, heavily influenced by their background. Thus, in the past due to the fact the opportunity to write history was only given to an elite and exclusive group of white males from the upper-class who has similar experiences and interests, the kinds of history being written suited their interests and a connection to the wider parts of the past was not achieved. However, due to increased rates of those given the opportunity to have a higher education in history, the demographic of those writing history has diversified. With this diversification comes wider interests and therefore a cumulative broader coverage of history, from different perspectives. Thus, a black and white ‘menu of history’ written by a very small demographic transforms into a more colourful one, with new connections to different pasts (displayed in Figure 3).

The uncloseable gap

The arguments thus far have been contingent on the fact that the study of history can successfully provide an objective account of the past. In fact, the ‘past’ and ‘history’ are two different things as it is nearly impossible to provide an objective account of the past, no matter how hard we may try. In his Pursuits of History, John Tosh explains part of this problem:

- A person’s values and assumptions are a product of individual experience and depend largely on societal conditions.

- The process of writing history requires a lot of decisions in order to get a finished product (e.g. choosing which sources to include, how to interpret sources, how one uses imagination to fill in the gaps of sources).

- Therefore, history can never be a completely objective account of the past

Another tendency in historical study is to create a satisfying account, with a distinct ‘beginning, middle and end’. Unfortunately, the past is not this convenient and clean; while some structuring must be done by the historian to make sense of this mess, there is a great risk of oversimplifying matters at the cost of real understanding in the process of making it a digestible story.

Moreover, historians may start studying a period with a particular hypothesis that appeals to them, and subconsciously only select evidence that supports their hypothesis, rather than analysing the sources in a way that may refute their model. For example, for a long time there was a fitting consensus that the Roman Empire had fallen due to a long-term economic decline, which complied with modern thinking on the economy being a key decider on a state’s health. However, an architectural discovery by Georges Tchalenko revealed that late Roman villages were prosperous and there was no major economic crisis before the 5th century, forcing historians of this period to reconsider their hypothesis. While this is an oversimplification in itself, it exemplifies the idea that our contemporary assumptions and stubbornness to support hypotheses can lead to explanations of the past that are simply not true and can cloud a real understanding and thus connection to the past.

Figure 3 illustrates this process, in which a formerly green irregular shape is turned into a turquoise regular (more satisfying) square by the observing historian. The two are not the same, and while we can try to minimise this barrier by consciously aiming to reduce the influence of our assumptions in our study of past and see it on its own terms, we are mere mortals and thus our understanding is capped at a point on the graph.

A false connection

In these ways it seems no matter how hard we try; we plateau at a point of the graph. However, there is a more Orwellian view that proclaims our historical understanding can be intentionally manipulated by those who create the history, due to the way they select and frame the evidence. This is particularly harmful when it comes to education as politicians can select certain narratives to teach the population through the national curriculum. This process is illustrated in figure 5. Hitler used the History curriculum as a propaganda tool to indoctrinate the youth such that they would form views in accordance to his ideology, with a nationalistic approach. For example, the German defeat in 1918 was explained as a work of Jewish and Marxist spies who had weakened the system from within and the hyperinflation of 1923 as the work of Jewish saboteurs. Similar methods are currently being used in North Korea based on ‘the thesis of Socialist education’, and even in Britain when in 2013 Michael Gove attempted (and failed) to reform the national curriculum with the intention of focusing on ‘Island story’ to make people proud of Britain without acknowledgement of its relationships with other countries. Such a curriculum could lead to a perversely insular perspective, which fails to equip students in a globalised world. Such a threat is becoming more potent in the age of social media, where leaders can tweet misinformation about the past and reach their audience at all times. Despite the fact I established that more people are able to gain a connection to the past now through education, this process manipulates the nature of the past, creating false and potentially harmful connections, which is arguably worse than no connection at all. Where this kind of connection lies on Figure 2 is less clear, or if it even lies in the negative y-axis in which our connection through history to the past has become so manipulated, any form of an authentic one cannot exist.

What does this all mean for our connection to the past and the extent to which we live in an ‘eternal present’? Despite the monotony over the last year of ‘wake up, zoom, sleep, repeat’ that can often make us feel as though we are living in a ‘Groundhog Day takes 2020/1’, a torturous eternal present, this is temporary and (hopefully) will be over by June 21st. Even so, throughout this ‘pestilence’ we have found time to study and appreciate history, with a surge of journalists drawing back on the history of pandemics and lockdowns to teach us, allowing us to draw parallels and establish a connection with the past. This exemplifies how fortunate we are to be born into a period of time in which a connection to the past is possible through the study of history, and that the masses have an increasing opportunity to understand the past. Nonetheless, the limits of historical knowledge prevent us from establishing 100% authentic connection, and perhaps we never will, and perhaps that’s not such a bad thing. This seemingly irritating gap between the graph line and the 100% ensures the debate that characterises and livens historical study persists, as never having consensus on a question means fruitful debate can occur. However, what is more concerning is leaders weaponising the past to create dishonest and harmful connections. Not only is this a disgrace to the study of history but has potential detrimental fallout. We must monitor how our leaders are trying to use history to instil a certain narrative and perspective, appreciating the value and the dangers of establishing connections with the past.